Chelsea vs. the third team: xG data may change the narrative around referee influence

Chelsea fans may be right in their assessment of Anthony Taylor’s refereeing. But if he's part of the "campaign against Chelsea," he's really bad at that, too.

Chelsea fans may be right in their assessment of Anthony Taylor’s refereeing: he’s at the bottom of the table for Premier League refs. Unfortunately for our beloved “campaign against Chelsea” narrative, his errors accrue to the Blues’ favor.

Everything about this article is unpleasant for me. I hate undermining arguments from people I like. I hate being the “WELL ACKSHUALLY, TEH DATA” guy. I hate the fact that I’m about to defend Anthony Taylor. And I really hate the fact that this article is going to be an “I told you guys” ammunition dump for a former colleague.

Unfortunately, that is to say, well actually, the data - my broad but admittedly shallow, single factor, somewhat hackish data analysis – indicates that Premier League referee Anthony Taylor is not part of the campaign against Chelsea.

FBRef has game-by-game expected goals (xG) data for the Premier League, La Liga, Bundesliga and Serie A (among others) starting with the 2017/18 season. For each game, I calculated the expected result based on each team’s xG: if the absolute value of the difference in xG’s < 1.0, the expected result is a draw. If one team’s xG is >1.0 their opponent’s xG, then that (former) team is expected to win and the latter expected to lose. I then generated expected points based on the expected result, so the difference between the expected result and the actual result turned into a point differential.

(Click here if you want to jump over the explanation and go right to the output)

What does this have to do with referees? Officials are sometimes called “the third team” on the pitch. That’s a bit jarring if you think match officials should be somewhere between neutral and robotic, and a bit worrisome if you think about what incentives for “winning” that might create for them. Regardless, enforcing the rules – even if done neutrally, robotically and accurately - does change the course of the game.

To what extent, then, could this third team influence games? And how and where might it show up quantitatively?

Expected goals reflect what should happen from a purely football perspective. Given these shots in these positions and whatever else the calculation factors in, this is the probability of the outcome. Expected goals should be among the most robust “regress to the mean” statistics: the xG of a shot doesn’t tell you too much about that shot. But the validity of xG should improve as you go from a shot, to a half, to a game, to all of a team’s games, to the league’s entire season, to multiple seasons across multiple leagues. As you add more games to the calculation, the influence of unusual events or transient conditions should approach zero: the goalkeeper committing a howler, a player scoring a worldie, a key player or entire team just having one of those days, a player receiving a red card in the first half, the effects of travel, the effects of injury, an unseasonably warm, dry night in Stoke.

All of that comes from and builds on 22 players on two teams. But 26 individuals (plus VAR?) on three teams decide the game.

The omission of the third team could, therefore, affect the accuracy of the expected result, even if not the accuracy of one team’s expected goals. Because their potential effect should be very small within an individual game, and because their performances can vary as much as the players’, we need to examine as broad a sample as possible and see if, in aggregate, certain teams teams or leagues deviate from their xG not because of their opponents, but because of the third team – specifically, the leader of the third team.

The key parameter I looked at, then, from over 1,900 Premier League games is the percentage of games in which the actual result was the same as the expected result, which I’ll call “result accuracy.”

“Expected results” discrepancies and the third team

By this measure, Chelsea fans are right: Anthony Taylor is uniquely bad. Among Premier League referees who have officiated more than 35 games (the median of English referees in the sample) since 2017/18, Taylor has the lowest result accuracy: 42%. That is about one-third lower than the referee with the highest result accuracy, Jon Moss at 60%.

Experience does not seem to have any effect on a referee’s result accuracy. Taylor was right 42% of the time in 150 games. Joining him in the relegation places are Martin Atkinson and Craig Pawson, who both have a 44% result accuracy on 141 and 124 games, respectively.

The top of the table is six referees with 54% or greater result accuracy over 100 games.

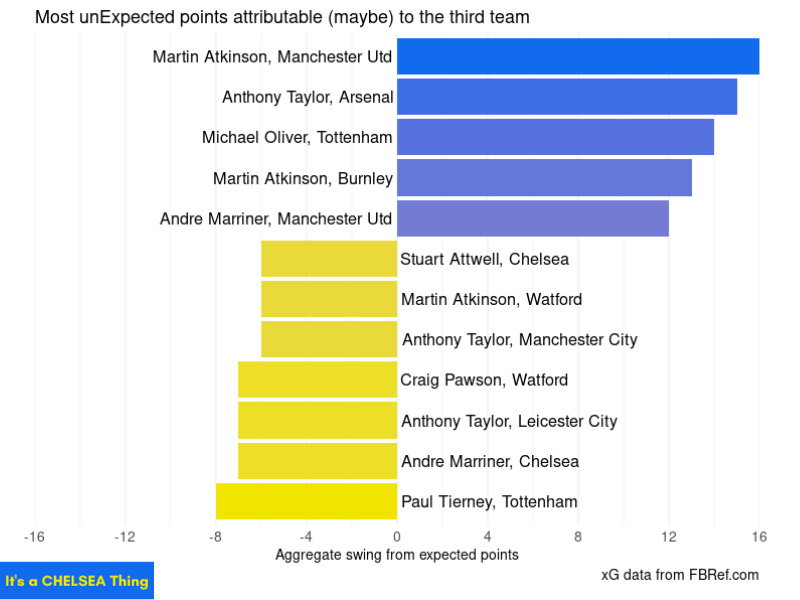

Converting expected and actual results to expected and actual points lets us assess how much a referee and his result accuracy can affect the table. Taylor’s result accuracy converts to 146 points going the wrong way – 27 of those in Chelsea games. Only Mike Dean has influenced more points for a single team, with 31 for Manchester United games. The top point tilts by referee and team include three for Man United (Dean, Moss and Atkinson), Taylor for Chelsea, Andre Marriner for Manchester City and Taylor with Liverpool.

This is where the narrative really gets data dank. Anthony Taylor’s rank incompetence accrued to Chelsea’s benefit. Not by much. The Blues have three more points from Taylor games than the xG’s indicated they would. David Coote and Paul Tierney are propa Chels, with the Blues taking an extra nine and eight points, respectively, from their games. And if any referees are part of the campaign against Chelsea, they are Stuart Attwell (-6) and Andre Marriner (-7).

This data dive comes with a pyramid of caveats. Admittedly, this approach is a bit hacktastic. Normally, I’m the first one to dismiss anyone who performs a single factor analysis, especially in something as complex as sports environments. Yet here I am connecting expected results to referee performance. That points to another consideration that may highlight my hackishness or my insight (or both, in equal parts).

The fundamental inputs I used – expected goals – are independent of the parties in question: the referees. That’s not good study design. If there are referee performance data out there, the leagues and the match officials’ associations guard them stringently.

But we’re looking to explain disparities that arise from those fundamental inputs. If xG is accurate in goal probabilities because it has so many inputs, why is it so inaccurate in an interactive two-way model, i.e., the difference between the teams’ xG vs. the difference between actual goals? Under that framing, we have to assess factors that are not in those inputs. The independence of the referees from xG means they could, in fact, be a contributor to those disparities.

That, though, brings us to another situation where we have to ask whether the data undercuts the narrative or if the narrative is built on facts that undercut our approach.

Not many Premier League fans and pundits celebrate the quality of the officiating. Those of us who watch other European domestic leagues, the Champions League or Europa League often marvel at the efficiency and accuracy of non-English referees. FIFA seems to agree with our assessment, as FIFA did not select any English referees for the 2018 World Cup.

But if we are making the case that result accuracy reflects to some extent the quality of refereeing, then we need to point out that the Premier League’s result accuracy (50.62%) is on par with the Bundesliga’s (51.51% over 1,561 games), and both are significantly higher than Serie A’s and La Liga’s (48.49% and 47.76%, respectively, over 1,920 games).

Transparent “third team” data will boost trust and performance

Football takes an archaic view on authority. Football’s governing bodies seem to think that the sport’s on-field authorities - the referees - derive their authority from perceived infallibility. They believe a referee, league or governing body compromises their place in the game by admitting routine errors. We see this by how rarely leagues or associations acknowledge errors, how egregious those errors have to be for them to do so and the fact that referees never publicly admit mistakes until after they retire.

The culture has moved on from that, in large part because relevant information is accessible to all. When we can all see the same replays that the referee sees at the VAR monitor, when we can compare the letter of the law to the events of the day, when we can review population-level data, everyone can determine what happened and judge the accuracy or veracity of any authority’s claim. When the person in charge continues to deny their demonstrable error, they look some combination of ignorant, malevolent, incompetent and hubristic. None of which are qualities anyone wants in a leader, neutral arbiter or colleague - all of which are ways to describe a referee’s relationship to the teams, players and the game.

Referees submit reports after every game and do a match review during the week with a more senior referee.

Open the books. Whatever quantitative measures, objective or subjective, go into those assessments should be a matter of public review. We’ve already seen the game. The only new thing anyone on the outside would learn would be about the actual craft and profession of officiating: what do they look for, what are their decision-making processes, how do they go about interpreting and implementing the rules of the game in real time?

That would help analysts, fans and pundits understand the officials’ role much better, and would lead to better informed analyses and perspectives (and less need for hackish data analyses. Please subscribe). And it would greatly reduce the suspicion and acrimony that surrounds certain referee-team pairings.

People have a greater appreciation of players’ physical abilities given the various ways we can see into professional athletes’ training routines. We have more respect for coaches and the profession when they take the opportunity to talk about their work in their terms. The third group in any game - the third team - could only benefit from doing the same.

Transparency only ever leads to improved quality and accountability, two things all fans in all sports demand from their officials.